I’ve been intrigued by book spine stories for a while. I probably first saw them through LibraryThing’s contests (which they call bookpiles). Then recently, I was tagged in a wave of Facebook chain posts asking me to “list 10 books which have stuck with you.”

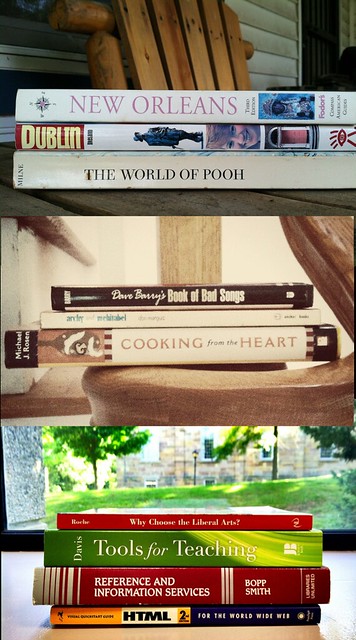

I saw the call for TDC 984 while I was at work. Looking over at my bookshelf, I saw my professional history – a paraprofessional job coding HTML, a transition into reference librarianship, a core text of instructional design, and all the while, a commitment to the broad liberal arts. So I played with different ways of arranging them in my window (it’s work, boss, honest) and snapped a picture with the Flickr app.

Rereading the instructions, it occurred to me that this is something like a Cubist exercise – it’s a picture of me, abstracted from 3 different angles at once. Obviously I didn’t achieve that with the visual style, but the realization helped me decide that I wanted to present different parts of myself more than I wanted to play with the poetic or narrative power of book titles.

The middle panel is just 3 things I like – cooking and storytelling,  poetry, and broad humor. The shot is taken on the staircase in my home, largely because the exercise had reminded me of Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2).

poetry, and broad humor. The shot is taken on the staircase in my home, largely because the exercise had reminded me of Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2).

Backgrounds are important in these shots – out the window of my office, the staircase, the top panel, which is about my wife and myself, is on our porch. They contribute to the story as much as the titles do. I used the Flickr app’s preloaded filters to get the colors where I wanted them. It felt a bit like a cheat compared to actually understanding how to set color levels, but it’s a start.

I got frustrated trying to figure out how to arrange the three pictures in GIMP. The importance I’d ascribed to the backgrounds fought with the collage arrangements I imagined. Ultimately I decided to go vertical on the grounds that a finished imperfect create beats a perfect one which never gets published.

I’m not entirely clear if it’s supposed to be read top-to-bottom or bottom-to-top… it hasn’t told me yet.

I had a fair amount of trouble with the “truthiness” of the process. Some of the images in that movie are actual shots of the day in question. Some are other shots of our trip, or of New Orleans. Some are

I had a fair amount of trouble with the “truthiness” of the process. Some of the images in that movie are actual shots of the day in question. Some are other shots of our trip, or of New Orleans. Some are  That’s why it’s in portrait orientation, and a weak attempt at perspective. It’s a personal view of the Internet – not an attempt to reflect what I know about the whole web, but how I think of my place in it. It reflects how I spend my time; it also reflects priorities in the way I use the Internet. (And of course, it reflects the way I wish to portray those things.) It’s also, really, a map of the Web, not the Internet. Notice that there’s no App Store, that I think of “email” as “the web” and not a separate thing anymore, that there’s no Netflix or Amazon Prime (which I watch through my Roku and TV, rarely my laptop or phone), that I don’t even think about protocols other that HTTP anymore.

That’s why it’s in portrait orientation, and a weak attempt at perspective. It’s a personal view of the Internet – not an attempt to reflect what I know about the whole web, but how I think of my place in it. It reflects how I spend my time; it also reflects priorities in the way I use the Internet. (And of course, it reflects the way I wish to portray those things.) It’s also, really, a map of the Web, not the Internet. Notice that there’s no App Store, that I think of “email” as “the web” and not a separate thing anymore, that there’s no Netflix or Amazon Prime (which I watch through my Roku and TV, rarely my laptop or phone), that I don’t even think about protocols other that HTTP anymore.